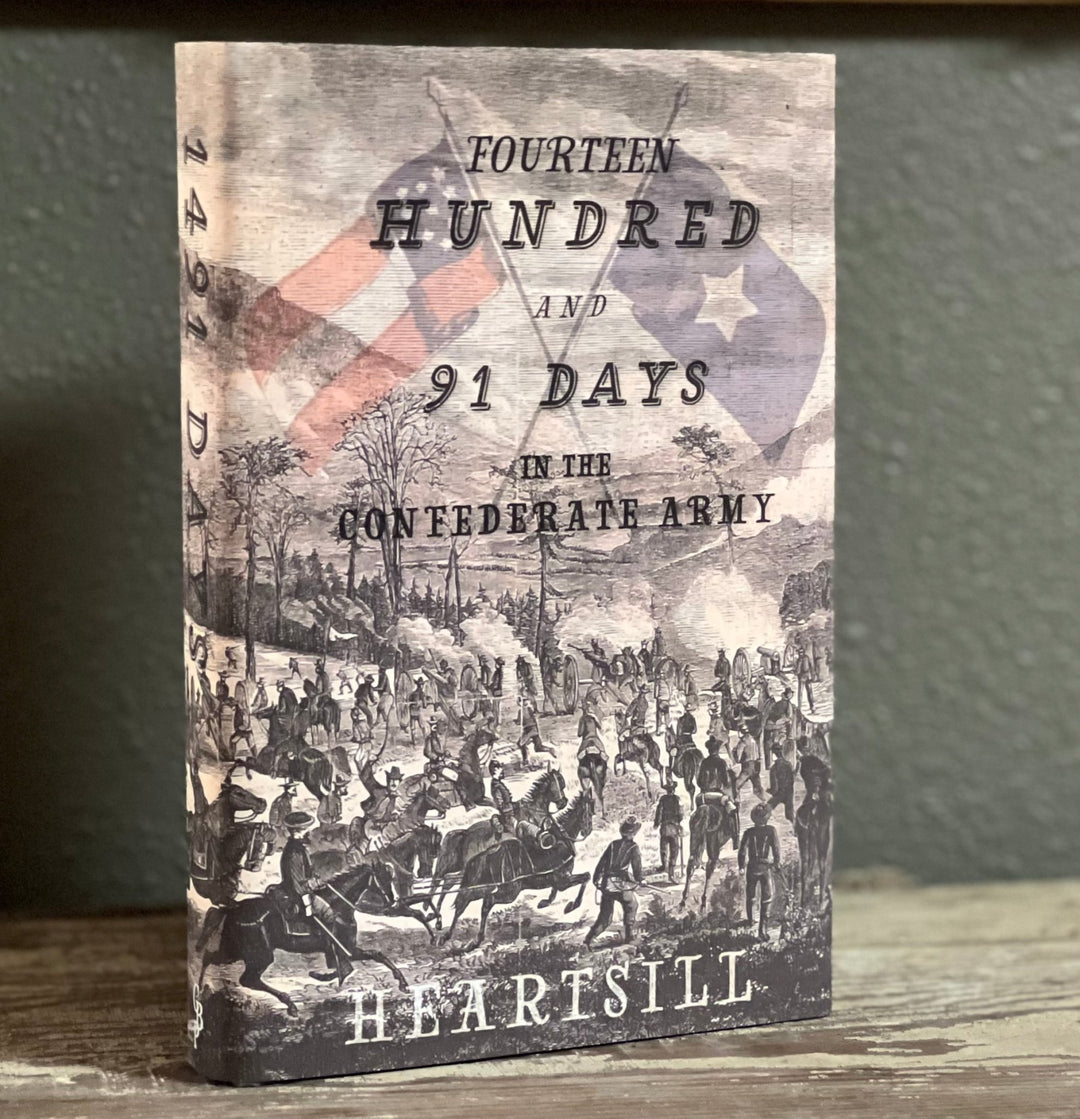

1491 Days in the Confederate Army by W. W. Heartsill

Imagine you spent fourteen hundred and ninety-one days fighting the bloodiest war in your country’s history.

And while you were fighting in and witnessing the ravages of war, you wrote down what happened . . . each and every day . . . while it was all still fresh in your memory.

That’s what young William Willitson Heartsill, a store clerk from Marshall, did from April 19, 1861 to May 20, 1865.

Heartsill was twenty-one years old when a big war started. He decided to join the army and became a private in Walter P. Lane's Rangers - official name: Company F, 2nd Regiment, Texas Cavalry, led by Colonel Rip Ford.

At the beginning of the war, the W. P. Lane Rangers stayed in Texas, guarding against Indian attacks on the western frontier. Heartsill’s writing about this time gives us rare insight into ranching, Texas frontier forts, the Indians, Mexican affairs, and the natural glory of western Texas. During their service in Texas, however, the boys were itching to go fight beyond the borders of Texas.

In 1862, they got their wish. The 2nd Texas Cavalry was sent to Arkansas. Not long after, they saw combat at Arkansas Post. Heartsill and his comrades were captured by Union forces and taken to Illinois.

He and some of his messmates were kept as prisoners at Camp Butler during the winter of 1863. He writes with all the heart a man can muster about the brutal cold and the heartbreak of watching his comrades enter the smallpox hospital one day, only to be removed to the dead-house the next.

In April 1863, they moved by train to Baltimore, then by boat to Virginia, where they were exchanged for Union soldiers held by the Confederates.

Heartsill and some of his unit were then attached to Braxton Bragg’s army in Tennessee. Now the cavalrymen comprised a makeshift infantry unit which they called "The Irregulars." Heartsill’s account of the Battle of Chickamauga and its aftermath is unforgettable.

But the Texans didn't like their new assignment under Bragg. Texas Rangers ordered to fight on foot are the very definition of disgruntled. Marching day and night in inclement weather was a shock for men accustomed to the cavalry service.

That and being assigned to officers not of their own choosing led them to take drastic action. In November 1863 the unit began to drift away, a few at a time, with a plan to regroup in Marshall.

Heartsill and three of his compatriots walked 730 miles in 47 days. When they got to the Mississippi River, they pulled the flooring out of an old cabin, caulked it with cotton and whittled three oars with their pocket knives. Their vessel, dubbed the "Lady King" got them safely down the river. The three ragged Texans made it to Marshall the day before Christmas Eve, 1863.

After six weeks of recuperation, the well-travelled Texans who had rendezvoused at Marshall were ready for action once again. They dubbed themselves “The Johnson Spy Company, Unaffiliated,” and set out for Tyler. There they joined up with Col. C. L. Morgan and were cavalrymen once again.

The war came to an end for them on May 20, 1865 while they were hunting deserters in East Texas. Col. William H. Parsons informed them the war was over and, “You are once again citizens of Texas.”

All this time Heartsill had been filling his journal with what happened every single day. 1491 days in all. When he filled a notebook, he sent it home for safekeeping and began a new one.

It’s no minor miracle that they all made it back to Marshall. In order for us to have his journal in book form, both he AND the journals had to survive the Civil War. Here's why:

In 1874, William Heartsill was the proprietor of a grocery store and saddle shop in Marshall when he decided it was time to make use of his jottings.

He ordered an Octovo Novelty Press from a catalog. That’s a foot-operated printing press which is about one step above a child’s toy. The project, which occupied all his spare minutes, was to turn all those notebooks into a printed book. Actually, one hundred copies of a printed book.

For each page he set the type. If you don’t know, that means assembling each word, letter by tiny metal letter, backwards.

Once the entire page was set, it was placed in the press and inked with a rubber roller. A fresh piece of paper was placed on the platen and the foot pedal pressed. That’s one. Now re-ink the type and do it again. Another nine-nine times. That’s one page down.

Now break up the type and set the next page, backwards, with those tiny metal letters. Heartsill had a total of 265 pages of type to set, each of which he had to ink and print one hundred times. 26,500 total inkings and pressings.

But William Heartsill was not content with such an easy project. He wanted his book to be illustrated with the likenesses of his brothers-in-arms, many of whom died in the war. So he wrote to them/their families asking for photographs. Sixty-one complied. Unfortunately, reproducing photographs was beyond the technical capability of the little Octavo Novelty Press.

So what was Heartsill to do? He had one hundred photographic copies made of each photo his friends had sent him. 6100 photographs in total, which he hand pasted into his books.

When the job was done he had 100 copies to distribute, no two quite the same.

William Hearstill’s creation is the rarest and most sought after book on the Civil War. When a worn copy hit the auction block in 2022 it was hammered down for $19,000.00. A signed copy sold in 2020 for $56,000.

There have been a few reprint editions over the last seventy years, and they have all become rather pricey in their own right. The problem with the reprints is that they were all facsimiles - copies of Heartill's original handiwork. That's fine if you want to view an example of what a cheap 19th century printing press could do, but it’s not fine for precisely the same reason.

Those tiny metal letters? They wear down with use and they don't wear down uniformly. That makes for missing and broken letters on the printed page...not so good if you want to read it. Every crack and oddity of the type is reproduced in those facsimiles. Plus, Heartsill had a limited number of commas in his type set, so when he ran out he turned to semi-colons and even apostrophes.

All of those visual speed bumps make for tough reading. One reader commented, “This could have been a fascinating read but the printing makes it extremely difficult to get through. I finally just put it down; the eyestrain wasn't worth it.”

That’s why I decided to completely reset the type for the Copano Bay Press edition. This is a book that people want to read, that deserves to be read, and shouldn’t be painful to read.

I had to work from two different existing copies in order to decipher every page to make this new edition. Now you can experience Heartsill's adventures, heartbreaks, victories and losses without tripping over broken letters.

The full title is:

Fourteen Hundred and 91 Days in the Confederate Army: A Journal Kept for Four Years, One Month and One Day: or, Camp Life, Day-By-Day of the W. P. Lane Rangers from April 19th, 1861 to May 20th, 1865

That's quite a title. I guess that's fitting, because it is quite a book.

Physical Details

- Fourteen Hundred and 91 Days in the Confederate Army

- 418 pages

- Standard edition hardcover in satin-finish jacket